Entity-Component-System (ECS) is a type of game architecture that focuses on composing entities with data only components, and processing logic separately in systems. Though, while working on my own little game engine, I noticed that a lot of the methods presented for implementing ECS frameworks are not trivial.

Often using this type of architecture people become obsessed with speed and efficiency, and don’t get me wrong, this is a goal. But it shouldn’t be your primary goal, especially making small games. In trying to get the best performance you often end up making something overcomplicated, which just isn’t going to make your life easier. This frustrated me, I like simple solutions, partly because they’re easier to work with, but also because they’re easier to tailor to my specific problems.

In this article I’ll briefly go over the ECS framework, and then dive into how to create a very simple version of it.

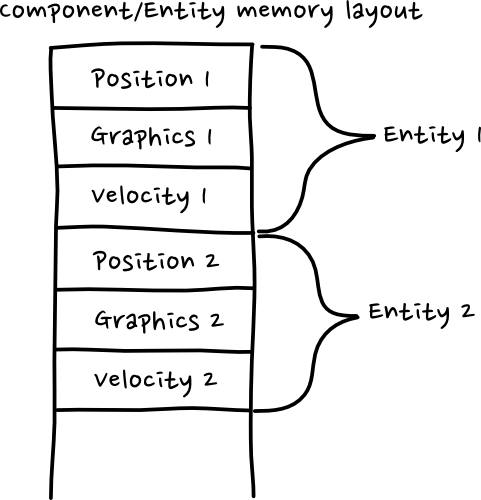

You might be familiar with the more object oriented approach to component systems. In which entities, or game-objects are bags that store a list of components. These components supply some data and behavior to the entity. This has a couple of problems. You could take one entity at a time, looping over each component. This makes certain kinds of optimizations hard though, like multithreading. Also you end up jumping around in memory as you go between each entity and likely between each component.

Another option is to update all components of a specific type, but because each entity owns the component data, they’re stored in different places in memory. So as you process each component you’re jumping around in memory again.

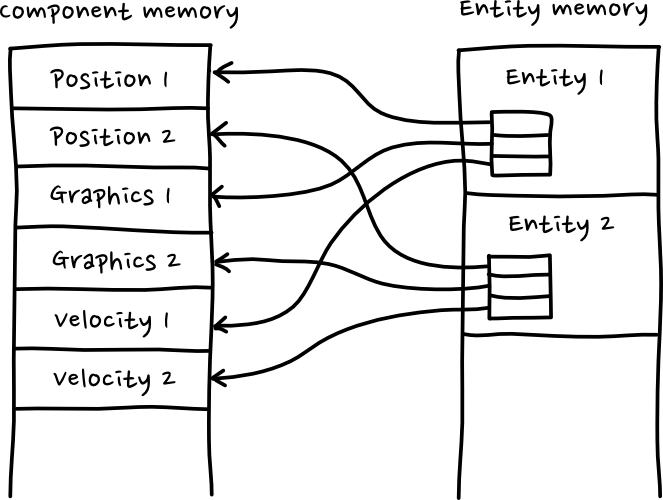

You could take ownership of the component data away from the entities, and store them in contiguous memory for each type, and then each entity stores a list of pointers to components it’s tied to. This is definitely better for performance, assuming you’re updating components per type. With regards to code organisation though, this still isn’t ideal.

A core idea in object-oriented programming is that data is encapsulated in objects that operate on that data. But in games, entities have data that a huge amount of systems are interested in. The position of an entity for example is used by the graphics system, physics system, AI system, etc etc. What happens in practice is that the data is shared between many systems, coupling them together and breaking the encapsulation that is core to OOP. If done incorrectly this can lead messy code. ECS solve this by separating the data and the logic.

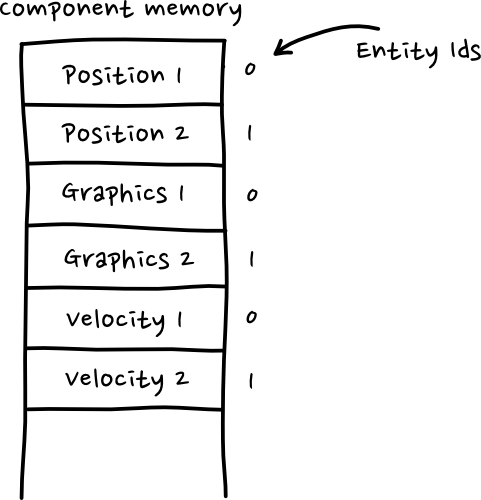

With ECS, an entity just becomes an index that lets you look up components assigned to that entity. The logic then moves out, and it operates on the components. An entity becomes a loose concept at this point as most systems only operate on subsets of components. This gives us massive opportunity to optimize our data access for the specific problem the system is trying to solve, this is the actual beauty of this architecture, and what I’d like to focus on with this implementation of an ECS framework.

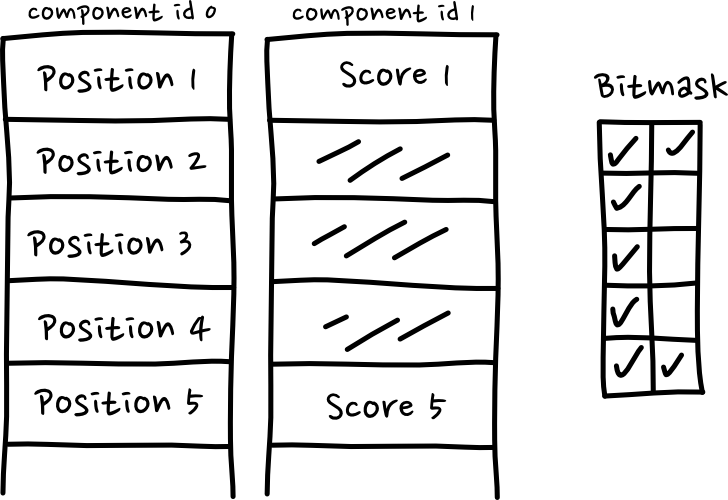

The core idea with the approach we’ll be taking is that each entity is just an ID number and a bitmask. Each component has an type ID, and we can use the bitmask to find out what components an entity has.

The components are stored in plain old memory pools, and we can use the entity index to retrieve the actual component data. The scene view wraps an iterator which will loop through the entities, checking which have the correct component mask, and returning those entity IDs.

Hopefully we’re all on the same page as to what an ECS is. Before we get into implementing it lets take a look at what it’s like to use an ECS, and by extension what we’re aiming to have at the end of the article.

Components are just plain old data, so creating them is super simple.

struct Transform

{

vec3 pos;

};

struct Shape

{

vec3 color;

};

We then create a scene, which will contain our database of components and help us access and manage it. We can create new entities, which returns an EntityID, just a number. And then assign components to each entity.

Scene scene;

// To create entities and assign entities to them do this:

EntityID triangle = scene.NewEntity();

Transform* pTransform = scene.Assign<Transform>(triangle);

Shape* pShape = scene.Assign<Shape>(triangle);

EntityID circle = scene.NewEntity();

scene.Assign<Shape>(circle);

Systems are just functions. You provide them with the scene, and they can “view” a section of the scene with a SceneView, providing what components they’re interested in. You then do whatever processing the system needs to do.

void ShipControlSystemUpdate(Scene& scene, float deltaTime)

{

// Loop over the entities you're interested in

for (EntityID ent : SceneView<Transform, CShape>(scene))

{

Transform* pTransform = scene.Get<Transform>(ent);

Shape* pShape = scene.Get<Shape>(ent);

// Do stuff

}

}

// Update the system by simply calling it with the current scene

ShipControlSystem(scene, deltaTime);

Lets start with component IDs. We need a way to numerically identify each component type such that we can set their place in a bitmask. A way to do this is with a static counter for each type specialization of a function.

extern int s_componentCounter;

template <class T>

int GetId()

{

static int s_componentId = s_componentCounter++;

return s_componentId;

}

Define int s_componentCounter = 0;, and then we can use it like this:

struct TransformComponent

{

float position{ 1.0f };

float rotation{ 2.0f };

};

int main()

{

printf("TransformComponent ID: %i\n", GetId<TransformComponent>());

}

Each time you call this on a new component type you’ll get another unique ID number.

Moving on, we need info about our entities. Entities are just an ID number, and a bitmask, so lets store that info in our new Scene type.

// Some typedefs to aid in reading

typedef unsigned long long EntityID;

const int MAX_COMPONENTS = 32;

typedef std::bitset<MAX_COMPONENTS> ComponentMask;

struct Scene

{

// All the information we need about each entity

struct EntityDesc

{

EntityID id;

ComponentMask mask;

};

std::vector<EntityDesc> entities;

};

You may ask why we need to store the ID as well, as it’s also the index into the vector itself. This has to do with how we’re going to deal with deleting entities, I’ll get back to that later, but for now don’t worry about it.

Creating entities is as simple as adding a new element to the list of entities:

EntityID NewEntity()

{

entities.push_back({ entities.size(), ComponentMask() });

return entities.back().id;

}

Assigning a component to an entity is also really simple at this point, we just set the bit corresponding to that component in that entities mask.

template<typename T>

void Assign(EntityID id)

{

int componentId = GetId<T>();

entities[id].mask.set(componentId);

}

Likewise removing a component is as simple as unsetting that bit. Now we have some basic tools available to us.

Scene scene;

EntityID newEnt = scene.NewEntity();

scene.Assign<TransformComponent>(newEnt);

Obviously no actual component data was created, that’s our next step. We need a memory pool to store the component data.

Component pools are nothing but memory pools, nothing really special. We store an array of char, since we don’t know the size of the pool at compile time. We dynamically create and destroy the entire pool. We’ll manually construct objects inside the pool when assigning components to entities. other than that we give you a nicer way to get the data at a specific index.

struct ComponentPool

{

ComponentPool(size_t elementsize)

{

// We'll allocate enough memory to hold MAX_ENTITIES, each with element size

elementSize = elementsize;

pData = new char[elementSize * MAX_ENTITIES];

}

~ComponentPool()

{

delete[] pData;

}

inline void* get(size_t index)

{

// looking up the component at the desired index

return pData + index * elementSize;

}

char* pData{ nullptr };

size_t elementSize{ 0 };

};

Now when we assign a component to an entity, we can actually prepare data for the component in a memory pool. First though, lets give the scene a list of pools, one for each component type. We can index this array using the component IDs we created earlier. Just a simple std::vector<ComponentPool> componentPools; inside the Scene struct.

When we assign a component we have a few things to do. First, we check if there is a pool for this component. If not we resize the vector of pools. Usually we also need to create a new pool for this component as well. Second, we can use the placement new operator to call the constructor of the component at the correct memory location in the pool.

template<typename T>

T* Assign(EntityID id)

{

int componentId = GetId<T>();

if (componentPools.size() <= componentId) // Not enough component pool

{

componentPools.resize(componentId + 1, nullptr);

}

if (componentPools[componentId] == nullptr) // New component, make a new pool

{

componentPools[componentId] = new ComponentPool(sizeof(T));

}

// Looks up the component in the pool, and initializes it with placement new

T* pComponent = new (componentPools[componentId]->get(id)) T();

// Set the bit for this component to true and return the created component

entities[id].mask.set(componentId);

return pComponent;

}

Lastly, we’ll set the bitmask for that entity, and return the newly created component for use. Now we’re getting somewhere. Given an EntityID you can also retrieve the component very easily with a function like this in the Scene structure:

template<typename T>

T* Get(EntityID id)

{

int componentId = GetId<T>();

if (!entities[id].mask.test(componentId))

return nullptr;

T* pComponent = static_cast<T*>(componentPools[componentId]->get(id));

return pComponent;

}

We’ve achieved quite a lot, and so far the example is less than 100 lines of code. You could even use this as a bare bones ECS framework at this point. Systems would have to manually loop over the list of entities, checking the bitmask on every entity, which isn’t ideal, but it would work. There is one important missing feature though, deleting entities.

This might seem straightforward at first, you just remove the entity from the list of component masks. The problem is, when you create a new entity afterward, it’ll be in the same slot as a previously deleted entity. A reference to the old entity could attempt to access data, and end up accidentally accessing data from the new entity. These are subtle, scary bugs, so we’ll protect against them by adding an extra piece of info to entity IDs, a version number.

The idea is pretty simple, we have a 64 bit entity ID. So we’ll store the index of the entity in the top 32 bits, and the version number in the bottom 32 bits. We can wrap up these operations with some simple functions.

typedef unsigned int EntityIndex;

typedef unsigned int EntityVersion;

typedef unsigned long long EntityID;

inline EntityID CreateEntityId(EntityIndex index, EntityVersion version)

{

// Shift the index up 32, and put the version in the bottom

return ((EntityID)index << 32) | ((EntityID)version);

}

inline EntityIndex GetEntityIndex(EntityID id)

{

// Shift down 32 so we lose the version and get our index

return id >> 32;

}

inline EntityVersion GetEntityVersion(EntityID id)

{

// Cast to a 32 bit int to get our version number (loosing the top 32 bits)

return (EntityVersion)id;

}

inline bool IsEntityValid(EntityID id)

{

// Check if the index is our invalid index

return (id >> 32) != EntityIndex(-1);

}

#define INVALID_ENTITY CreateEntityId(EntityIndex(-1), 0)

This means all entity IDs are unique, assuming you don’t wrap around the 32 bit number. Which I feel is unlikely for indie game projects. We need to make some modifications to our older functions now to deal with this change. Anywhere we treated the ID as an index, we replace with GetEntityIndex(id). And we can add some additional checks to ensure we’re using the correct entity.

template<typename T>

void Remove(EntityID id)

{

// ensures you're not accessing an entity that has been deleted

if (entities[GetEntityIndex(id)].id != id)

return;

int componentId = GetId<T>();

entities[GetEntityIndex(id)].mask.reset(componentId);

}

I’ve added the above check to Remove, Get, and Assign. This is the reason we store the entity ID in alongside the component mask. It means we can very easily check if we’re actually accessing the right entity, as each ID is unique for the duration of execution.

Now we can return to deleting an entity. We don’t really want to adjust the IDs of any existing entities, nor do we want to resize the vector of entity descriptions. Instead we’ll keep a record of what entity IDs are “free” and can be used when creating new entities. This is as simple as a vector of EntityIndex’s, std::vector<EntityIndex> freeEntities;.

Deleting an entity now amounts to setting the entity slot to an invalid index, and incrementing the version number. Then add another element to the free list. We also clear the mask.

void DestroyEntity(EntityID id)

{

EntityID newID = CreateEntityId(EntityIndex(-1), GetEntityVersion(id) + 1);

entities[GetEntityIndex(id)].id = newID;

entities[GetEntityIndex(id)].mask.reset();

freeEntities.push_back(GetEntityIndex(id));

}

Now when we create a new entity, we can check the free list first, and if there is a free entity slot, just reuse that.

EntityID NewEntity()

{

if (!freeEntities.empty())

{

EntityIndex newIndex = freeEntities.back();

freeEntities.pop_back();

EntityID newID = CreateEntityId(newIndex, GetEntityVersion(entities[newIndex].id));

entities[newIndex].id = newID;

return entities[newIndex].id;

}

entities.push_back({ CreateEntityId(EntityIndex(entities.size()), 0), ComponentMask() });

return entities.back().id;

}

Notice that there are two cases for creating a new entity ID. If there is nothing in the free list, we’ll make a new ID with version number 0, if there is something in the free list, we’ll use the version number stored in there. Which we incremented when deleting the entity earlier.

That’s pretty much it! A very basic ECS framework that you can work from and expand to fit your game. There is just one extra thing I’d like to do, a convenience more than anything, and that’s SceneViews.

A scene view is something that wraps up the process of iterating over a set of components. When writing systems it’s a massive help as you can just specify what set of components you’d like to iterate over, and it will return an iterator for that set. Without it you’re faced with manually iterating the entities vector and checking the component mask of each entity manually for the set you’re interested in.

Our goal here is this interface:

for (EntityID ent : SceneView<Transform, CShape>(scene))

{

// Do stuff

}

We need to abide by the requirements of a C++ iterator to function like this, the basic minimum being this:

struct SceneView

{

SceneView()

{

}

struct Iterator

{

Iterator() {}

EntityID operator*() const

{

// give back the entityID we're currently at

}

bool operator==(const Iterator& other) const

{

// Compare two iterators

}

bool operator!=(const Iterator& other) const

{

// Similar to above

}

Iterator& operator++()

{

// Move the iterator forward

}

};

const Iterator begin() const

{

// Give an iterator to the beginning of this view

}

const Iterator end() const

{

// Give an iterator to the end of this view

}

};

Our job then just becomes filling in this structure to work how we need. Let start with telling the SceneView what components we’re interested in. This requires a variadic template. We’ll use a C++ 11 feature called parameter packs, and we’ll unpack it into an initializer list that we can use to set a component mask we store inside the SceneView.

template<typename... ComponentTypes>

struct SceneView

{

SceneView(Scene& scene) : pScene(&scene)

{

if (sizeof...(ComponentTypes) == 0)

{

all = true;

}

else

{

// Unpack the template parameters into an initializer list

int componentIds[] = { 0, GetId<ComponentTypes>() ... };

for (int i = 1; i < (sizeof...(ComponentTypes) + 1); i++)

componentMask.set(componentIds[i]);

}

}

// ... (omitted)

Scene* pScene{ nullptr };

ComponentMask componentMask;

bool all{ false };

}

I’ve done some extra bits here, namely taking in a reference to the scene, which we’ll need to access the entities, and also if the parameater pack size is 0, then we set a bool to true which lets us skip checking each entity later. It means that a SceneView defined with no parameters like, SceneView<>(scene), will just iterate all entities in the scene.

The iterator struct itself need to know everything such that it can move itself along in the scene, so that means it needs the scene itself, the component mask, and whether it’s just testing all. Of course it also needs the EntityIndex of it’s current location in the scene.

struct Iterator

{

Iterator(Scene* pScene, EntityIndex index, ComponentMask mask, bool all)

: pScene(pScene), index(index), mask(mask), all(all) {}

// ... (omitted)

EntityIndex index;

Scene* pScene;

ComponentMask mask;

bool all{ false };

};

We now have pretty much everything we need to start filling out the methods of the iterator. Dereferencing into the actual entityID is very simple, we can just use the index to lookup the ID.

EntityID operator*() const

{

return pScene->entities[index].id;

}

Checking equality with another iterator is also straightforward, just compare the indexes.

bool operator==(const Iterator& other) const

{

return index == other.index || index == pScene->entities.size();

}

bool operator!=(const Iterator& other) const

{

return index != other.index && index != pScene->entities.size();

}

Incrementing the iterator is where it gets a bit tricker. I spent a while fiddling with this to ensure you don’t get overruns or invalid indexes coming up. Checking for a valid index has been separated into it’s own little helper. We check if the EntityID itself is valid, since the iterator must skip over entities in the free list, and then it checks the mask to see if the entity has the right components.

bool ValidIndex()

{

return

// It's a valid entity ID

IsEntityValid(pScene->entities[index].id) &&

// It has the correct component mask

(all || mask == (mask & pScene->entities[index].mask));

}

Iterator& operator++()

{

do

{

index++;

} while (index < pScene->entities.size() && !ValidIndex());

return *this;

}

We’re almost there. Only two more functions to implement! We need the SceneView struct itself to return the begin iterator. Similar to operator++, we need to check for valid indices, and the component mask, since the first few entities might not have the correct set of components.

const Iterator begin() const

{

int firstIndex = 0;

while (firstIndex < pScene->entities.size() &&

(componentMask != (componentMask & pScene->entities[firstIndex].mask)

|| !IsEntityValid(pScene->entities[firstIndex].id)))

{

firstIndex++;

}

return Iterator(pScene, firstIndex, componentMask, all);

}

This will loop until the first entity that we’re interested in, and create an iterator of that index.

If this iterator supported going backward, we’d have to do something similar for end, but it doesn’t so it’s reasonable to just return the highest available entity index. This will stop the iterator from going any further.

const Iterator end() const

{

return Iterator(pScene, EntityIndex(pScene->entities.size()), componentMask, all);

}

And that’s it. We’re finished! The initial goal we set out near the start of this article has been achieved, and you can use this as a starting point to make your game. The entire implementation as I’ve described fits in 230 lines of code. You can browse the finished code here, and expand on it for your own use if you so please.

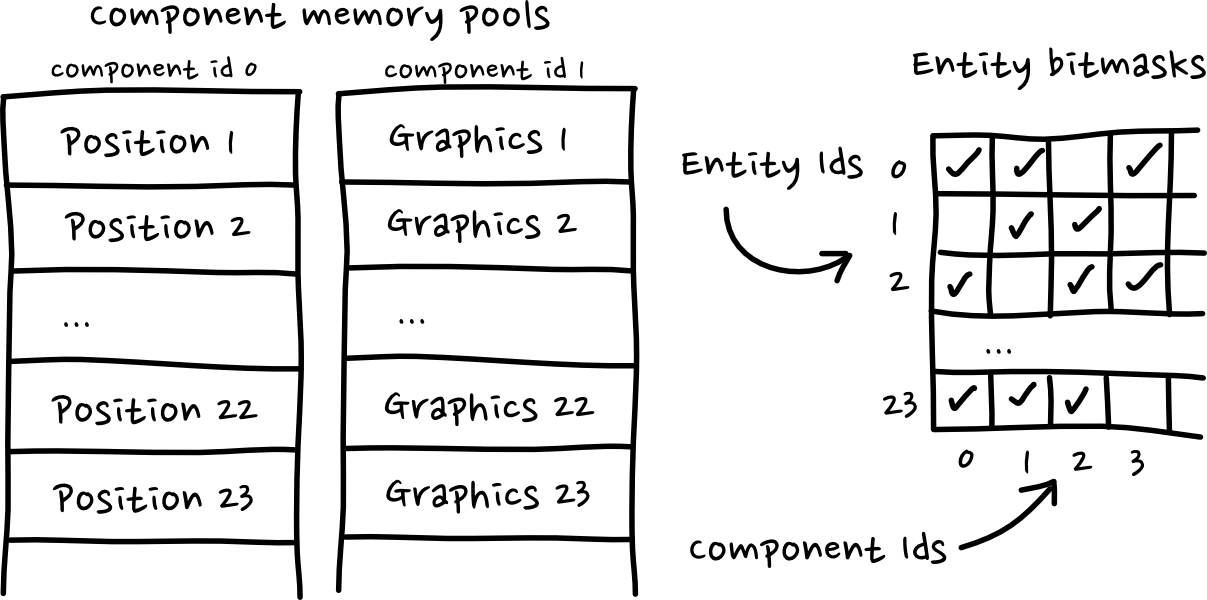

There is one small problem with this implementation, which you may have already noticed. We allocate memory for components that an entity might not be using. Here’s a picture to demonstrate:

As you see, if a certain component is used infrequently, we store enough memory for it to be on every entity, wasting a whole bunch of space. This is a problem, but the truth is, if you’re making small games, this isn’t much of an issue. It’s absolutely a solveable problem, but when you’re making small games, or you’re still trying to understand the problems your game is asking you to solve, this really isn’t a big deal.

The most performance benefit will be had when iterating over more tightly packed components, as there is less jumping around, and those sorts of components are generally the ones that benefit from the performance improvement anyway.

Having said that, if your game is starting to scale, and this is becoming a problem, here are two alternative ways of implementing an ECS that solve this.

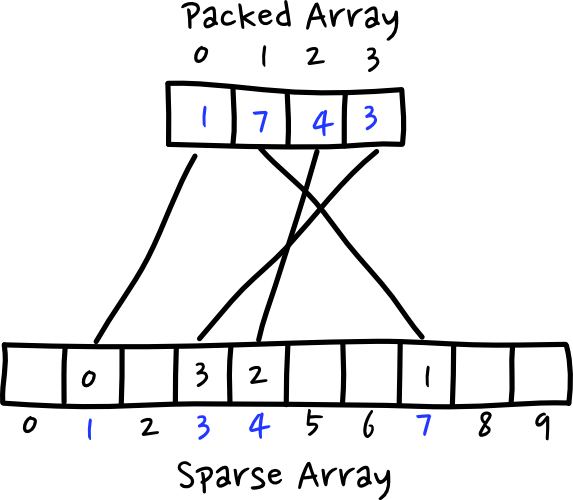

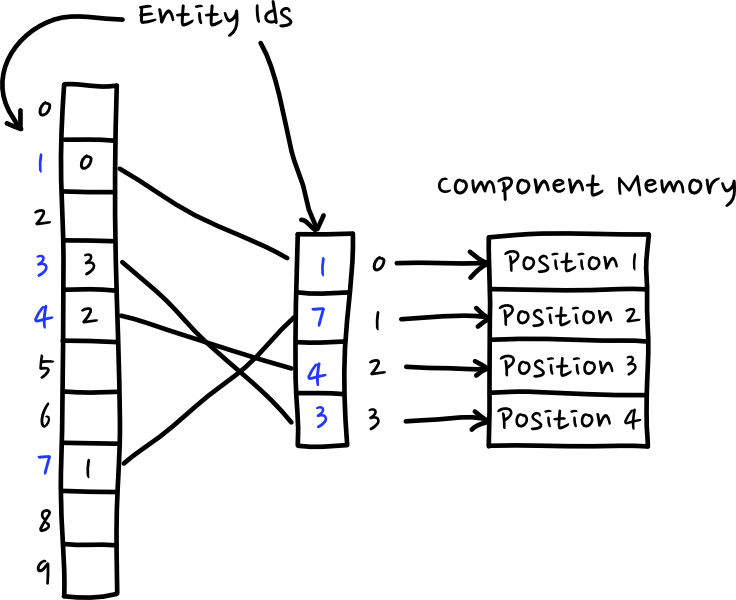

A sparse set is a way of mapping sparse indexes to a tightly packed array. It essentially amounts to two lists, one sparsely filled with indexes to the tightly packed list. And the packed list contains indexes back to the sparse list elements. A diagram might help this concept come across.

The way you use this in an ECS is that each component pool has a sparse set assigned to it. The sparse list of indices contains the actual indices in the memory pool that you can retrieve your component data from. The packed array contains a list of entity indices that have a component of this type assigned to them. This way you can do away with the bitmask, and use the sparse set both to access tightly packed memory, and to find out if an entity has a component assigned to it.

This obviously saves a huge amount of memory, but also component data is tightly packed and so iterating any one component is as fast as you can possibly get.

Another great benefit of this is that if you have a SceneView that iterates over two types of components, you simply loop through the array of the smallest component pool. Thus minimizing the amount of checks on each entity. For large scenes with lots of entities and components this is much faster. Probably as fast as you’ll ever need.

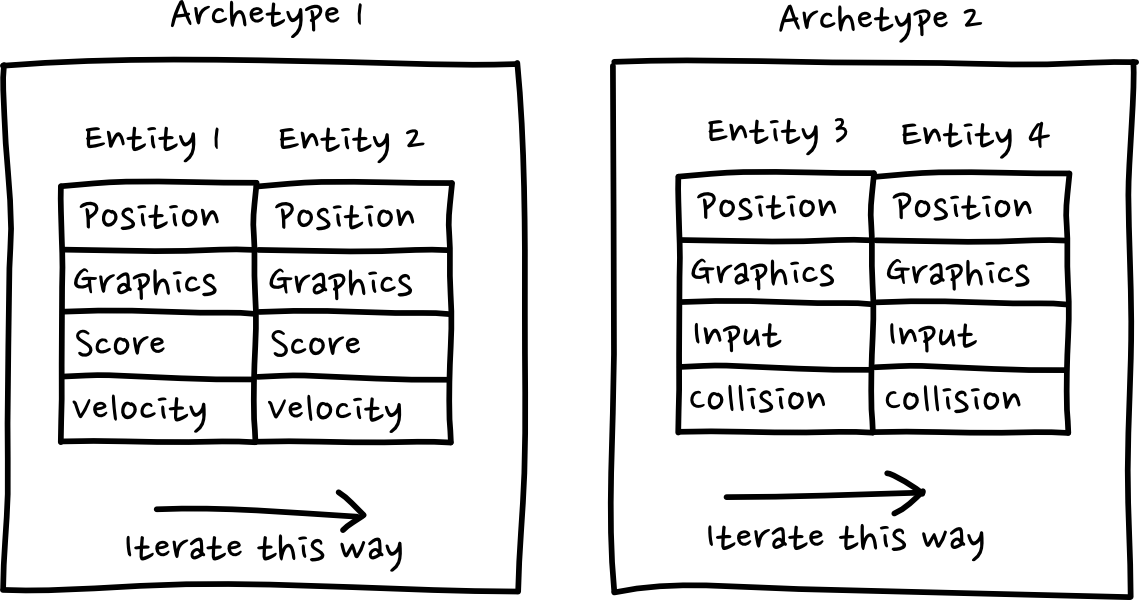

This type of ECS is the one that Unity is using in it’s Data-Oriented-Technology-Stack (DOTS), and so it’s quite popular at the moment. Rather than tightly packing component data, it instead focuses on keeping entities with similar sets of components together in memory. I found this to be the most complicated type of ECS to implement correctly.

The core idea is that all entities that have the same set of components are called an “archetype”, and are stored together in a contiguous array. Iterating over entities with a particular set of components, then becomes a case of iterating over the archetypes and then giving back all the entities in those matching archetypes. Assuming the amount of archetypes is much much less than the number of entities (you’d hope this is the case), iterating becomes extremely fast. There’s very little checking to do, and data is quite close together.

The downside to this is that adding and removing components from entities involves moving all the component data for that entity from one pool to another. Ideally you would structure your game so as to minimize the amount of component changes, and minimize the number of archetypes. Executing on this idea efficiently is not trivial, and I have not successfully implemented it myself.

My goal with this article was to give you a stepping stone to make your own small games with an ECS that you could easily adapt to your specific needs. You get the benefits of a game structured in this way, without the complexity that often comes with writing ECS frameworks. Hopefully I’ve achieved that. If you have any questions or suggestions let me know through my twitter @davecolson.